Words make you accountable

By Hamish Lyon

As the slow world of formal writing seems to fade into history, the question before us is whether architects will continue to write, as they have for centuries, or will memes and emojis become the universal measure of appreciation and success. There are many reasons why writing may be in decline, not least because it requires precision, clarity, grammar, punctuation and cognitive awareness. Good writing requires the capacity to synthesize complex ideas into a coherent written structure. None of this satisfies the voracious speed and appetite of social media.

Perhaps this is why the current perceived leaders of communication, at least in popular culture, are blue-tick Tweeters and Instagram influencers. The global explosion of commentary and debate that followed the permanent suspension of @RealDonaldTrump, for violating Twitter’s Glorification of Violence Policy, demonstrates just how deeply entrenched social media has become, even within the highest levels of government policy and international relations. In this case it also demonstrated how, whether published or tweeted, we are all inescapably accountable to the words we use.

But I have hope, beyond 280 characters. Vasari won’t go away that quickly, neither will Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture (1923) or Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City (1966). Jane Jacobs great contribution with The death and life of Great American Cities (1961) was a monument to conviction and the power of the written word. And who would have thought a clothing categorisation S, M, L, XL would be the title of an architectural treatise to explain late 20th century urbanism.

Words as currency

Given the current context of the global pandemic, many countries continue to face extended lockdowns with the daily news constantly reporting on models of contagion and death. Being confined to your house or apartment for an extended period has turned us all into news junkies. And while audiences for Netflix and other video-streaming services have boomed over this period, so too has the audience for the written word. The New York Times added 600,000 new subscribers over a single quarter, while in Australia the ABC, Guardian and Sydney Morning Herald and other mastheads have all reported huge audience growth over 2020. This demonstrates significant public trust and support for quality journalism.

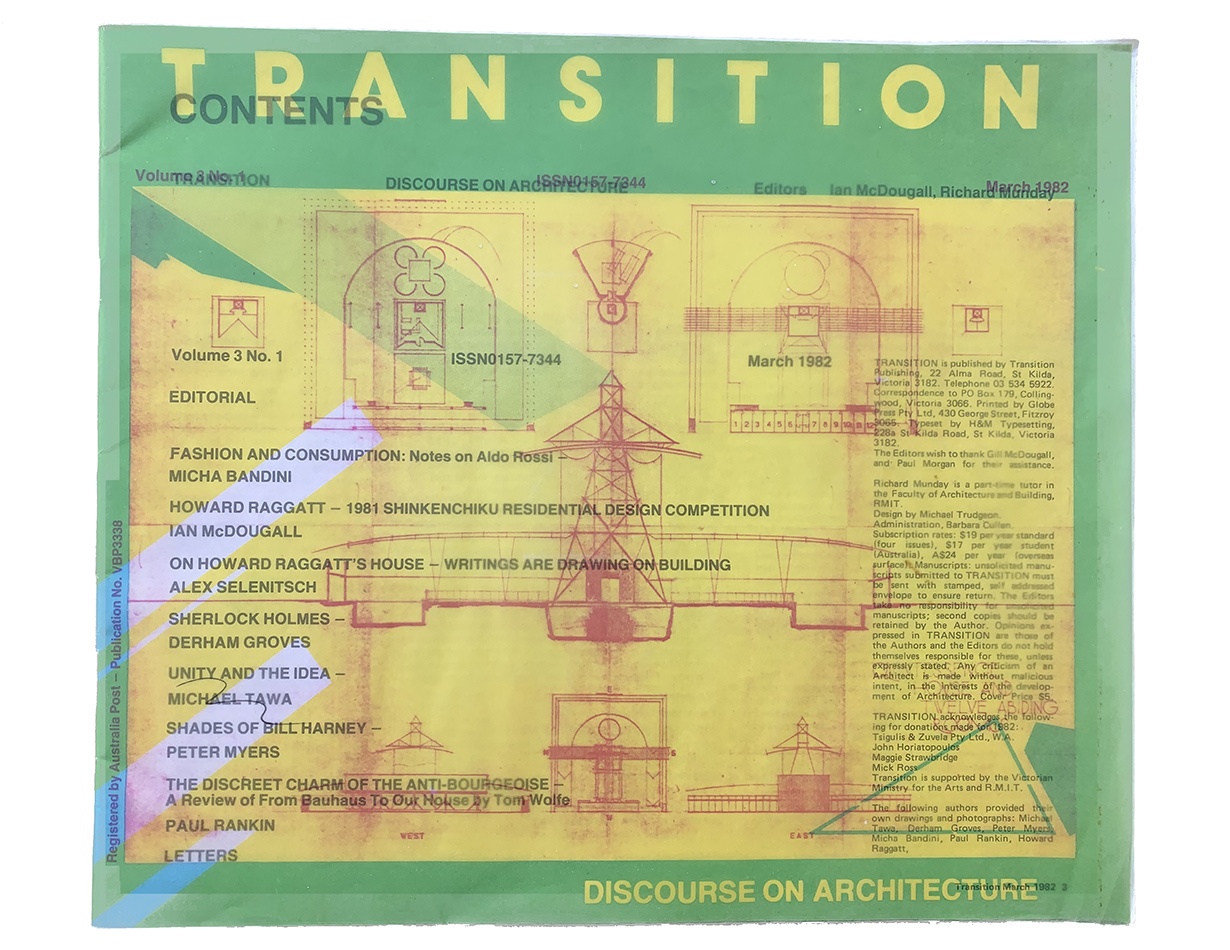

As a practicing architect, the work of the Australian Institute of Architects also clearly represents its national collective members. There are, however, fewer and fewer opportunities to write as part of a public debate. As an ardent student in the 1980s, I read, re-read, studied and engaged with every edition of Transition Magazine. It was one of a number of publications engaged with architectural polemic and contemporary political ideas. As an example, Ian MacDougall’s review of Howard Raggatt’s 1981 Japan Architect Magazine Competition (Shinkenchiku) for a house on the grounds of the Museum of the 20th century (a call for the ‘quintessence of the urban detached house’) was a clear case of ideology, political and religious support. Raggatt’s competition entry was based on a fervent and unwavering ideal that the Christian faith would prevail as the preferred model for future universal consumption. The entry proposed a model for the future suburban house, with the benefit of the 12 apostles camped out in lodgings in the back garden but under the guardianship of a high-voltage electrical pylon. A curious suburban dream.

Some 40 years later, I’m not sure these words would represent the current global religious or geo-political context. The ten-minute podcast or Ted Talk seems to be the current forum for ideology and religious dissemination. The important factor (for this student forty years ago) was that the written review was published for students to learn and develop their knowledge. The debate was both frozen in print and time, yet also allowed to develop over time.

The word and the sketch

When architects no longer write, ideas can drift into cartoon narratives. The Hollywood cliché of a masterpiece drawn on the back of a napkin is commonly seen as a creative, benign and non-political activity. It can, however, be corrosive to the community it intends to serve. Recently, this was placed into sharp focus by a Melbourne architect who erected large hand-drawn political placards in his front garden. Multiple illustrations were used to compare the Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, with the infamous dictator Adolf Hitler. Extreme, absurd, bizarre? Politics and historical facts aside, the association between the Holocaust death camps and the COVID-19 lockdown seemed an odd message for a Victorian community trying to emerge from a pandemic.

So why use this technique of caricature to demonstrate a political and ideological point of view? Perhaps because it is easy. Too easy. To reason and debate through the written word is difficult, complex, ambiguous, annoying. It takes time. Words require deep thought, historical perception and the possibility of being proven wrong. Words make the writer accountable.

Translating this to the world of architecture, there was once a time when the architect/patron relationship could be close and trusting, even for projects of great cost and complexity. In such a world an inspired sketch or parti was often all that was needed to win the commission. Today it is not that simple. More robust and analytic tools are needed.

From utopia to request for tender and back again

For the professional practice of architecture, both large and small, clarity of communication is of paramount importance. Although the precise definition of drawings, schedules and specifications are becoming ever more important, words remain the top of the legal list. If the words are not well crafted, architects can be condemned to being simply the purveyors of documents for the managing contractor and on occasion used against them for the purpose of litigation.

The written word, as documented intent, has always been the backbone of the practicing professional, whether the architect is delivering a house, a school, a hospital or even a major national infrastructure project. The irony and comedy of the ABC program Utopia reveals today’s reality. The constant reports and submissions that appear on (the main character) Tony’s desk every day highlights a true reflection of how public policy and project outcomes are interconnected. Despite the comedic background, the show illustrates that national, state and local policy can be made on the back of written recommendations. What is also sadly all too true in this all-too-real comedy, is the idea that, at the policy level, genuine writing has become replaced with slogans.

At a contractual level, current procurement process for most large public Infrastructure projects requires a complex multi-staged process that starts with an Expression of Interest (EOI) followed by a selected Request for Tender (RFT). The final tenders are required to respond to a complex series of pro-forma documents, schedules, spreadsheets and all within strict word limits. This tightly organised system produces, on the one hand, extreme limitations, while on the other the opportunity for creativity. Written text aimed at maximum benefit is not much different to an end of school exam. The over-used request for value-add, global engagement, or point of difference, means minor advantages must be utilised to maximum effect. Thankfully architects and the profession are still tenuously bound by a number of complex and legislated requirements, including the Architects Act (1991).

The Architects Act

The Architects Act remains the cornerstone of the practicing architect. It is the foundation of professional acumen. But to accord with its requirements the practicing architect must develop a range of skills, experiences and the ability to use the written word as a mechanism to engage with clients, managing contractor and a never-ending range of legal opinions. Evermore challenged by the emergence of contemporary procurement processes, such as Early Contractor Involvement, Design and Construct or Town Planning Drawings are good enough’, the Architects Act continues to support the need for clarity and the opportunity for architects to work from a defined scope of service – in writing. A well-crafted variation response or a forensic reply to a Request for Information from site, is the equivalent to a major design idea. The narrative in the responding text needs to be both persuasive and aware of ongoing liabilities. Sometimes writing is all that stands between a disastrous value-managed design variation and an architectural idea that is followed through to completion. Between failure and success.

Although architects are seen as simply a profession that draws the pictures to create a built object, the reality is far more complex. It requires the translation of information through a complex series of systems to mediate the quality of the final built outcome. These processes are a great benefit to architects who can find themselves on an equal footing with clients, managing contractors and sub-contractors, using written correspondence to overcome the old fashion idea that it was ‘lost in the mail’. Enormous server farms in the mid-west of the US now keep everything ever written and everyone somewhat equally liable.

Architect as future citizen

For these reasons the future of writing, not just as critical and cultural commentary, but as professional practice, must be defended. It must not be allowed to be stifled by convention, governance and legality. It remains the architect’s right to express their individual or collective ideas through writing. The necessity for communication via the virtual and digital platforms of Zoom, Teams and other programs has highlighted the need to make communication a vital part of operations. It also demonstrates that physical geography, locality and nationality has become less of a constraint.

The pandemic may yet leave a positive footprint. In learning to adapt to the new normal we may yet return to the solidity of words to record important ideas, rather than shifting distractedly through the perpetual blur of images on social media.

This article was first published in Architect Victoria May/June 2021: ‘Lost for Words’.

‘Lost for Words’ can be viewed online at the Victorian Chapter of the Architecture Institute of Australia website here.